By: Robyn Stewart, M.S.

Reviewed & Approved by Dr. Kylee Duberstein, UGA Assistant Professor

When it comes to equine behavior, there are a wide variety of topics we could discuss. The 2024 Equine Exchange Lunch and Learn taught a year-long curriculum on equine Behavior and Training, with the full playlist of recordings available here: https://kaltura.uga.edu/playlist/dedicated/1_15kqhbaq/. For the purposes of this article, I’d like to focus on how horses learn.

The foundation of most animal learning theory is behaviorism. Behaviorism is the idea that behaviors are responses to stimuli and that learning happens when specific behaviors become linked to specific consequences. For example, if you touch a hot stove, you immediately pull your hand away to avoid being burned. In this case, the hot stove is the stimulus, pulling away is the behavior, and the burn is the consequence. Learning happens when you connect the behavior to its outcome—since touching the stove results in pain, you are less likely to do it again.

Behaviorism also explains how behaviors and skills are developed. One key factor is repetition, known as the “law of use.” The more often you perform a behavior, the stronger the connection between the action and its consequence. Another factor is trial and error. Sometimes, we don’t know what the outcome of a behavior will be until we try it. If the result is desirable, we are more likely to repeat the behavior – if the result is undesirable, we are not likely to repeat it.

Two important techniques of behaviorism are shaping and chaining. Shaping involves reinforcing approximations or attempts at a single behavior, and is most effective for developing new behaviors. For example, when teaching a horse to pick up its hooves for cleaning, you may reward the behavior of shifting weight off that leg, then for slightly lifting the hoof, then for holding it up long enough for it to be cleaned. Shaping is the process through which you reward each “try” or attempt at the desired behavior. Chaining is similar to shaping, but on a larger scale. Chaining links learned behaviors into a specific sequence, and is most effective when teaching complex tasks. For example, if we want the horse to learn to turn on the haunches, we might first teach the horse how to move forward, then how to move its shoulder away from pressure, then how to spiral in on a circle, then to turn on the pivot foot. Each of those behaviors has to be learned separately before the horse can link them together into the desired final outcome.

When it comes to how horses learn, several behavior-based theories or methods can be applied. One of these is classical conditioning, a concept developed by Ivan Pavlov in the 19th century. Classical conditioning follows an if-then pattern: if a new stimulus occurs, then a new behavior follows. With repeated exposure, the response becomes more frequent or automatic as the animal learns to expect the outcome. This type of learning involves involuntary or reflexive behaviors. For example, if your horses get excited every time they hear the feed room door open, they have developed a classically conditioned response.

Operant conditioning is a teaching and learning theory first developed by B.F. Skinner in 1937. This theory states that a stimulus and behavior occur together and that the behavior can be conditioned to become more or less likely over time. If a behavior is not reinforced, it may weaken until it eventually disappears—a process known as extinction.

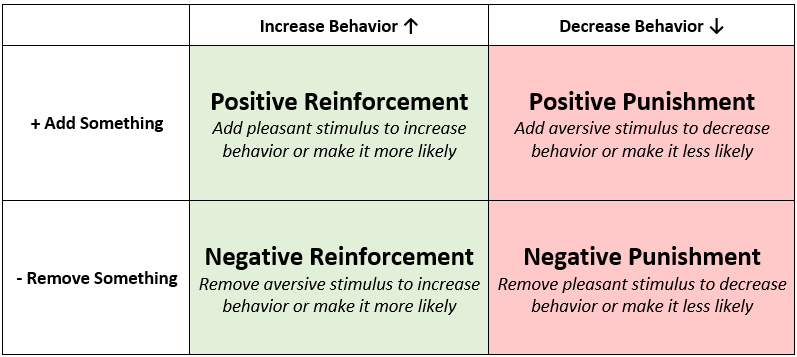

In operant conditioning, behaviors are shaped through positive or negative reinforcement and punishment, which either encourage or discourage certain actions. Punishment is anything that makes a behavior less likely to occur, and reinforcement is anything that makes a behavior more likely to occur. Positive means the learner is given something, and negative means the learner has something taken away. This framework forms four options: positive punishment, negative punishment, positive reinforcement, and negative reinforcement.

Punishment is anything that makes a behavior less likely to occur. In positive punishment, the learner is given something to make a behavior less likely or frequent. This method can decrease undesirable behaviors because the horse learns to associate the behavior with a negative consequence. In horses, this is often the addition of pressure in response to an unwanted behavior. For example, if a horse crowds the gate and we use a lead rope or whip to move the horse away, we are ADDING pressure (lead rope or whip) to REDUCE the behavior of gate crowding. Negative punishment is when something pleasant is taken away from the horse in order to make a behavior less frequent. It can also be the lack of reward for a behavior. One example (though a bad one) would be if you withhold feed if a horse acts up in the show ring. You are removing something pleasant (feed) in order to reduce behavior (bad performance). Negative punishment isn’t very effective in horses due to their less developed prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex is an area of the brain that controls complex thinking like problem-solving and long-term planning. Horses don’t have the same ability to reason and plan as humans do – they don’t necessarily link the consequence of action with a behavior. While we can reason that we removed the horses feed because of it’s performance in the show pen, the horse does not have the ability to connect those two events.

In contrast to punishment, reinforcement is anything that makes a behavior more likely to occur. In positive reinforcement, the learner is given something rewarding to increase the likelihood of a behavior occurring. For horses, we often use primary reinforcers like food or treats, which tend to produce stronger responses than secondary reinforcers (such as clickers, scratches, or vocal cues). Typically, we use primary reinforcers (food) as the main reward, while secondary reinforcers act as a “bridge” or a way to mark the correct behavior until the primary reward can be given.

To make secondary reinforcers effective, we may need to use classical conditioning to help the horse associate them with something positive. For instance, a clicker is initially a neutral stimulus—it doesn’t mean anything to the horse. But when the sound of the clicker is paired with a food reward, the horse begins to associate the click with the treat. Over time, the clicker itself becomes a positive reinforcer. In the future, whenever the horse performs a desired behavior and hears the clicker, it will reinforce that behavior. For example, if we want our horse to come to us, we might whistle (stimulus). When the horse starts moving toward us (desired behavior), we use a secondary reinforcer, like a verbal “yes” or a clicker, to mark the behavior until the horse reaches us and we can give a food treat (primary reinforcement). In this way, we add the reward to increase the behavior of coming when called – an example of positive reinforcement.

Negative reinforcement, on the other hand, means the removal of something to increase the likelihood of a behavior. In horse training, this is often referred to as pressure and release. It’s important to note that pressure in this case is not punishment. For example, if we ask a horse to halt by pulling back on the reins (stimulus), and the horse stops moving (desired behavior), we release the pressure on the reins. Similarly, when asking a horse to walk off using pressure from both legs, we soften the pressure as soon as the horse moves forward, removing the discomfort. This release of pressure encourages the horse to repeat the behavior in the future.

Understanding how horses learn is essential for effective training and addressing behavioral issues. Persistent behavioral problems may signal underlying health or management concerns. Conflict behaviors—such as tail-swishing, bit-chomping, refusal, bucking, kicking, bolting, and rearing—are often signs that a horse is experiencing physical or mental discomfort. These behaviors are the horse’s way of expressing resistance to handling or training cues and are some of the clearest ways a horse can get our attention. While it is easy to blame the horse for “misbehaving,” these behaviors typically arise when the horse is unable to predict or control the stimulus being applied. In horse training, we continuously present stimuli that the horse must interpret and respond to.

Conflict behaviors often stem from the improper application of reinforcement or punishment. This could involve poor timing of pressure and release, rewarding inconsistent responses, or not rewarding approximations of the desired behavior. For effective training, the stimuli we use should be escapable, predictable, and controllable. When these conditions aren’t met, the horse becomes insecure and anxious, which may further contribute to undesirable behaviors.

A combination of positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement is commonly used in horse training. Reinforcement is typically much more effective than punishment because it guides the horse toward the correct behavior, rather than just suppressing an unwanted one. Punishment, while it can help stop certain undesirable behaviors, doesn’t provide clear guidance about the correct behavior the horse should perform. Without that clarity, it’s more difficult for the horse to learn and repeat the desired action. For example, positive punishment (like adding pressure when a horse misbehaves) can be effective in eliminating unwanted behaviors such as biting or kicking, but it doesn’t necessarily teach the horse what to do instead.

In contrast, reinforcement works by rewarding correct and expected behaviors, which encourages the horse to repeat them. The timing of reinforcement is critical—it must be immediate and accurate. Delayed reinforcement can cause confusion, as the horse may not associate the reward with the behavior you’re trying to reinforce. For example, if you reward a horse too late, it may not understand what action is being reinforced, diminishing the effectiveness of the training. Additionally, incorrect reinforcement can strengthen undesired behaviors. For instance, if a horse reacts strongly to being fly-sprayed by rearing, spinning, or kicking, and you remove the fly spray stimulus because the behavior scared you, you’ve unintentionally reinforced the negative behavior. The horse learns that reacting strongly leads to the removal of the discomfort, which can escalate the unwanted behavior. Similarly, if a horse kicks the stall door at feeding time and you feed him more quickly in response, you’ve reinforced the stall-kicking behavior.

Finally, consistency is key in training. The desired behavior must be reinforced each time it occurs so the horse knows exactly what is expected of them. Since everyone trains horses differently, it’s important to understand that not all horses will immediately recognize the specific behavior expected of them when introduced to a new person or situation. Successful training requires patience and repetition to ensure that the horse can reliably recognize and respond to cues as intended.